As someone interested both in the world of mechanical watches and in the world of patents, as this blog clearly shows, I have recently acquired a mechanical watch that brings these two worlds together. That purchase has encouraged me to return to this blog, which I had somewhat neglected lately due to lack of time.

This is a rather unusual mechanical watch, one that immediately catches the eye because it departs from what most people instinctively picture when they think of a mechanical watch.

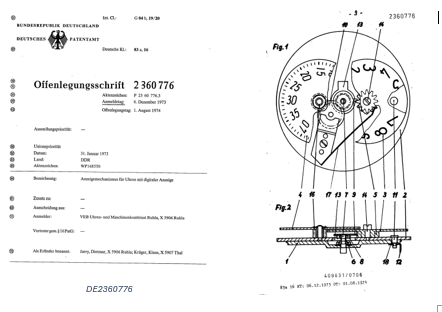

More specifically, it is the UMF Ruhla 1434-3, fitted with the calibre 24-34-2. This type of watch is known as a Scheibenuhr (disc watch), also referred to as a jumping-hour watch. In this design, the time is not displayed by hands but by digits: the hour digit jumps once every sixty minutes, precisely when the minute disc completes a full 360-degree rotation

This watch has a history that began more than fifty years ago in a country that has not existed since 1989: the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). In 1973, VEB Uhrenwerke Ruhla (now Uhren- und Maschinenfabrik Ruhla) launched the watch known as the Ruhla Digi 73—a purely mechanical wristwatch with a “digital” display based on discs. Instead of hands, the time was shown through windows, with an hour disc that advanced instantaneously every sixty minutes: a true jumping hour.

Ruhla Digi 73

From a technical point of view, this was not merely an aesthetic choice. Driving a jumping-hour disc reliably requires controlled energy accumulation, precise release, and exact synchronization with the minute train. Uhrenwerke Ruhla solved this challenge with its calibre 24-34, a movement with a pin-lever escapement, designed for industrial robustness, ease of manufacture, and low maintenance—typical priorities in a planned economy such as that of the GDR.

This mechanism was protected by a patent, DD106483A1, with family members filed in the Federal Republic of Germany (DE2360776A1) and in France (FR2216611A1).

It may seem surprising that a communist state operated a patent system and even had a patent office. Yet, although the socio-economic context differed greatly from that of market-economy countries, the patent system fulfilled several fundamental functions:

- documenting and classifying technical advances,

- recognizing the work of inventors,

- facilitating exports and licensing, and

- structuring technological progress within state-owned industry.

The fact that patent protection was extended to West Germany and France clearly shows an intention to support exports. In fact, around 60% of the company’s production was destined for Western and Asian markets.

The fact that, more than fifty years later, a replica, or at least a model clearly inspired by the original, has been produced using the patent as a reference demonstrates that the patent document has fully achieved its objectives of structuring technological progress and documenting and classifying technical advances. In particular, it has fulfilled one of the core functions of the patent system: contributing to the dissemination of technological information. Although the patent expired decades ago and the State that granted it no longer exists, the technical knowledge remains alive in the patent document, where the requirement of sufficiency of disclosure is made tangible. On the back of the new watch, there is an explicit reference to the GDR patent 106483.

This reference to the patent on which the mechanism of the new version of the Ruhla Digi 73 is based also connects with an earlier blog entry entitled “PATENT PENDING: WHEN A PATENT BECOMES A VERY POWERFUL ADVERTISING TOOL.”

The new UMF Ruhla 1434-3, calibre 24-34-2, does not exactly reproduce the mechanism described in the original patent document. The current movement is more sophisticated, incorporating a lever escapement and jewels. Likewise, the case is made of steel and the crystal is sapphire, whereas the original GDR model used a chrome-plated brass case and plexiglass instead of a crystal.

This singular watch highlights the strength of the patent system and the technological and historical relevance of patent documents: a system that existed in a communist state and that, more than half a century later, still makes it possible for a patent granted in that context to serve as the basis for manufacturing a modern watch, thanks to the technological information disclosed at the time in the patent document.

Leopoldo Belda Soriano

One thought on “TECHNOLOGICAL INFORMATION IN PATENTS: AN EXAMPLE OF RESILIENCE”