In a previous post devoted to the PCT International Searching Authorities, allocating enough time to the search and examination of patent files was already highlighted as one of the key elements to achieve a high quality examination, which would be of paramount importance in a situation of free competition among the 23 PCT International Searching and Examining Authorities. An implementation of a proposal by the Indian Patent Office already analyzed would bring about such free competition.

Despite the importance of that factor, there is a huge lack of transparency about it among the main Patent Offices of the world. From time to time, some offices decide to redefine the production requirements their examiners must comply with, usually in order to cope with increasing backlogs. In that situation it would be desirable to carry out a benchmarking survey of the time allocated to examination in various patents offices. However, this is an almost impossible task due to the lack of data available. There is only one outstanding exception: The USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office).

The USPTO has never concealed its data about how many hours its patent examiners are allocated for the examination of a patent application. This has made it possible for researchers to carry out surveys on this issue. A new one has been recently published: “Michael D. Frakes & Melissa F. Wasserman, Irrational Ignorance at the Patent Office, 72 Vanderbilt Law Review (forthcoming 2019).”

The goal of the article is to try to check whether a previous article “Rational Ignorance at the Patent Office” by Lemley (2001) was right to conclude that “the costs of giving examiners more time outweighs the benefits of doing so”.

Michael D. Frakes and Melissa F. Wasserman have concluded in their work the opposite of what Lemley had stated: “society would be better off investing more resources in the agency to improve patent quality than relying upon ex-post litigation to weed out invalid patents”, and those additional resources can be summed up in “more time allocated to the examination of patent applications”.

The article states that “On average, a U.S. patent examiner spends only nineteen hours reviewing an application, including reading the application, searching for prior art, comparing the prior art with the application, writing a rejection, responding to the patent applicant’s arguments, and often conducting an interview with the applicant’s attorney.”

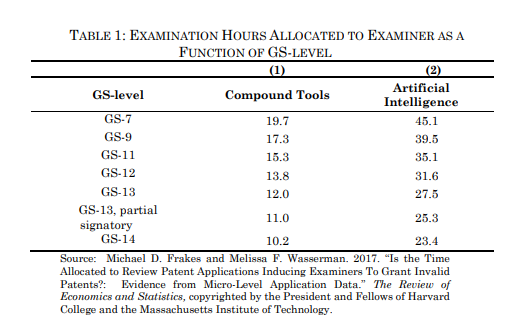

In one of the tables provided by the authors (see below), one can notice that at the USPTO there is a professional career for patent examiners (a key element to prevent a high turnover in the workforce) with several levels.

It is observed as well that the time new examiners are given to carry out the search and examination is halved when they reach the highest level. The time allocated also varies depending on the technological sector: 19,7 hours for “compound tools” and 45,1 hours for “Artificial Intelligence”.

Following new estimates, the article demonstrates that the savings in future litigation costs outweigh the costs of increasing examiner time allocations.

All those who have examined patent applications will agree that to some extent the more time available the better the quality achieved. However, there is also agreement that once a threshold is exceeded, the improvement attained is insignificant .

The authors estimate the cost of increasing the time allocated for search and examination and the costs that higher litigation caused by low quality patents represent. Once compared, and unlike the results of the 2001 article, the costs brought about by further litigation outweigh the costs linked to better examination.

The result of this survey confirms that the amendment of the Spanish Patent Act (Ley 24/2015) that came into force two years ago was well founded, since its purpose was to prevent low quality patents from being granted in order to reduce litigation and thus uncertainty for third parties. However, due to the parallel existence of utility models, where patent rights are granted on inventions without substantive examination and with a pre-grant opposition procedure, in Spain we are witnessing a shift of patent applications towards utility models. Thus, the bubble of low-quality patents has not been completely burst. One could say utility models provide a loophole in the rule.A similar move is about to be taken in France, where assessment of inventive step is going to be introduced in the patent granting procedure.

Conclusion

The article by Michael D. Frakes and Melissa W. Wasserman provides solid arguments in favour of a high-quality substantive examination, carried out by specialized examiners. Despite the high cost that keeping a high-standard patent office might entail, this is clearly outweighed by the legal certainty provided.

Proofread by Ben Roadway

Leopoldo Belda-Soriano