The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) can be considered one of the great international success stories of the patent system. Although it is far from achieving what would be called the “world patent”, in other words, that from a single patent application one could get a patent with worldwide effect, it considerably facilitates the extension of patent protection to a large number of states. I will not go into what the PCT consists of, as potential readers of this post will be well aware of its preliminary nature, and that it is up to the national or regional patent offices to grant or refuse patents.

The world map available on the WIPO website shows three large areas where the blue colour is not visible, corresponding to the 157 contracting states of the PCT. They represent 81% of the member states of the United Nations and it should be noted that many of the absent states are archipelagos or islands in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. If we exclude those microstates, the three major areas absent from the PCT are:

– South America: Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina.

– Central and East Africa: Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea.

– South Asia: Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Myanmar.

However, in the rest of this article I will focus on South America, and more specifically on Argentina and Uruguay, where I believe the great anomaly lies, given the characteristics of both countries.

Unlike the rest of these states that do not yet participate in the PCT, the standard of living is much higher in Argentina and Uruguay, and they do not have the characteristics of political instability, war, or extreme poverty that are found in the other states.

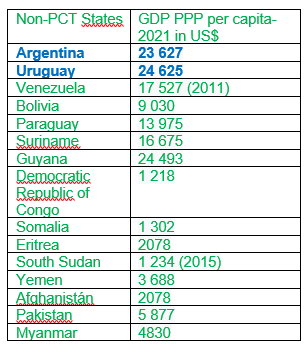

Below is a table showing the GDP PPP of the countries absent from the PCT.

It can be seen that the GDP PPP of Argentina and Uruguay is considerably higher than that of the other non-PCT countries, with the exception of Guyana, a country with a population of about 800,000 inhabitants. It can therefore be concluded that, in terms of economic development, Argentina and Uruguay are an anomaly among the non-Contracting States to the PCT.

As a patent professional working with PCT international applications, I have noticed that there is a demand from Argentinean and Uruguayan applicants for membership of the PCT. It is not uncommon for applicants of Argentinean and Uruguayan origin to use the PCT. Nevertheless, as filing a PCT international application requires the applicant to be a national or resident of a PCT Contracting State, they do so by including a national of a PCT Member State as an applicant, even if only for some countries where they do not intend to enter the national phase later on. Here are two examples:

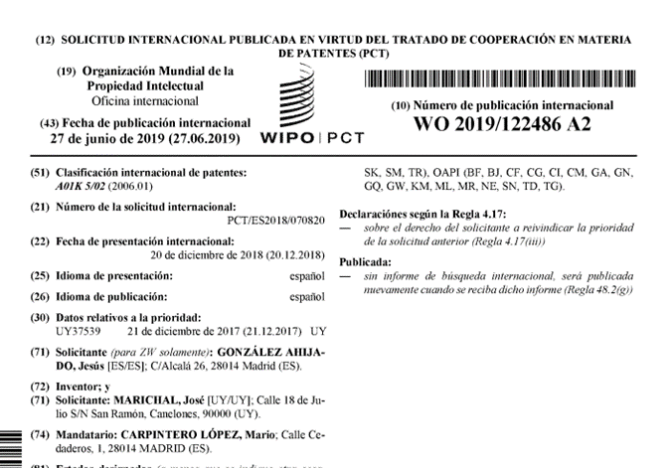

Example of a Uruguayan applicant that includes in the PCT application a Spanish national as applicant. The Spanish applicant works in the industrial property agency processing the application: WO2019122486A2

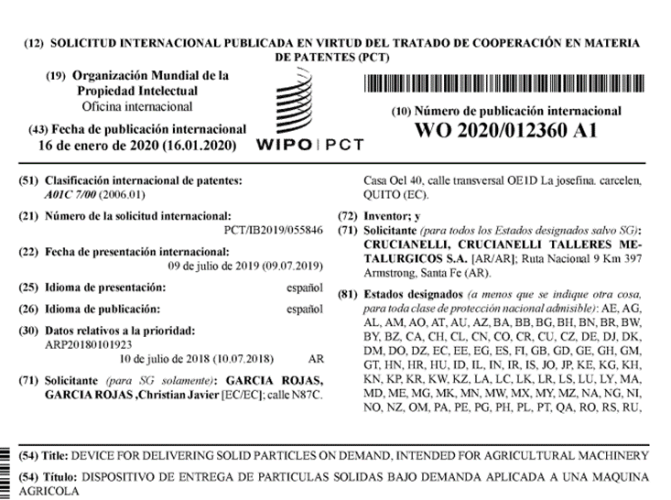

And here is an example of an Argentinian applicant who included an Ecuadorian national as applicant in his PCT application:WO2020012360A1

Both the Argentinean and Uruguayan economies have innovative companies that would undoubtedly benefit if their countries were PCT Contracting States. They would be able to apply for these PCT international applications without the need to introduce outsiders as applicants.

An article has recently been published in the Argentinian newspaper “La Nación” about a successful Argentinian entrepreneur of Korean origin, Dante Choi. He has filed a patent in the United States and China on the electric boiler mentioned in the article. Had he been able to use the PCT it would probably have simplified the prosecution and perhaps protection would have been extended to more states.

Having shown that there are inventors in both countries who would benefit from PCT membership, the immediate question is why they are not yet part of the treaty.

In this article published in 2019 in an Argentinian online newspaper dedicated to the pharmaceutical sector, the Uruguayan patent expert José Antonio Villamil explains in detail why he does not consider it appropriate for his country to join the PCT. The key lies in the pharma sector. In Uruguay, the demand for medicines is supplied by national laboratories. This is a strategic sector and its opposition to Uruguay joining the treaty should be taken into account. Although this is not explicitly stated, the usual arguments against multinational pharmaceutical companies are used, such as the use of the phenomena known as “evergreening” and “patent thicket”. It is also argued that, given that Uruguay is a technology-importing state, where the number of patents generated is much lower than the number of patents obtained by foreigners, entry into the treaty would mainly favour technology-exporting states. It is also argued that, if any Uruguayan applicant needs to use the PCT, they will always be able to do so, although the problems related to nationality are omitted, a stumbling block easily overcome as we have seen above. These last two arguments have also been used by European states such as Spain and Poland to justify not joining the project known as the “unitary patent” or “European patent with unitary effects”.

Another argument used in order not to join the PCT is that the authority in charge of patent examination (DNPI in Uruguay and INPI in Argentina) lacks the necessary resources to examine the considerable increase in the number of patent applications that would be filed if it were to join the PCT. In addition, it is pointed out that the large patent offices, known as International Search Authorities (ISAs), which prepare the IBIs or International Search Reports, have permissive criteria in the evaluation of patentability requirements.

In 2017, Uruguay’s accession to the PCT was discussed in parliament under the Frente Amplio government, but the proposal failed. In this article published in a Uruguayan newspaper it is clear that the Uruguayan pharmaceutical lobby played a key role in the proposal not being approved. As shown by the statements of the president of the ALN (Association of National Laboratories):

“Alfredo Antía, president of the ALN, said that it will lead to an increase in the price of medicines and recalled that the national pharmaceutical industry provides 90% of the products consumed in the country. Guillermo Arrospide, vice-president of the CNFF, said that in 2014 there were 215,000 patent applications worldwide under the treaty. “Can you imagine if that number of patent applications fell on the Uruguayan market? “

The same arguments have been put forward in Argentina, and as an example is this article by the Fundación Argentina GEP

Also in both countries, there have been advocates for PCT membership. In this blog post written by attorney Rocío Gendra of the Industrial Property Agency Herrero y Asociados (Argentina) dated August 2021, the advantages that access to the PCT would bring to the Argentine innovation system are explained. On the other hand, it is understandable that industrial property agents in Uruguay and Argentina are in favour of joining the PCT because of the business opportunities it would open up for them.

According to Rocío Gendra, the reasons behind Argentina’s non-incorporation into the PCT are as follows:

“The real reasons behind the position of the opponents of accession are not the defence of national sovereignty, or the protection of the public interest (such as the right to health), but the free access to technology and innovation, which result from an incalculable investment by third parties, to satisfy purely personal and commercial interests”.

Among those in favour of Uruguay joining the PCT is Uruguayan IP and trade expert Carlos Mazal who has made several statements on the subject: https://youtu.be/mA8OiSP7aJc, Post | LinkedIn.

Carlos Mazal considers that joining the PCT is fundamental for a Uruguayan economy that must be based on biotechnological innovation applied to agriculture and cattle-raising, in which this small country is a powerhouse. This small size also obliges it to sign free trade agreements and PCT membership will be a requirement in those agreements, as will be seen below.

Pro-accession sectors regularly organise events, such as the one in this article held last April (2022). The PCT beneficial aspects were highlighted and a Uruguayan innovator, the doctor and musician Daniel Drexler took part. He turns out to be the applicant and inventor of two PCT applications: WO2014210463A1 and WO2012167234A1, and claimed to have had to overcome numerous problems to protect his inventions abroad due to Uruguay’s non-membership of the PCT. Looking at the bibliographic data of his applications, one can guess that he had to include US companies as applicants.

In recent years there have periodically been rumours of an imminent incorporation of these countries into the PCT, as in 2016 or in 2018 or in 2017, as seen above, when the issue was even debated in the Uruguayan parliament, but the accession did not happen.

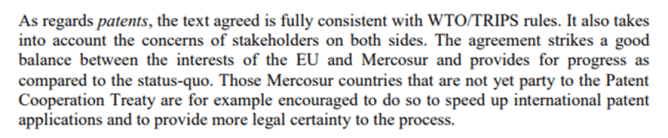

In June 2019, a free trade agreement between MERCOSUR (to which three of the Latin-American countries absent from the PCT – Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina – belong) and the European Union was announced.

The agreement has not yet entered into force, as it still has to be approved by the European Parliament, the parliaments of the EU member states and the parliaments of the MERCOSUR countries. Ratification of the agreement by the various parties does not seem to be easy. Motions against it have been passed in some European parliaments (Ireland, the Netherlands, Austria, and Belgium).

The text of the agreement includes a few lines devoted to the PCT agreement, indicating that MERCOSUR states will be encouraged to join the treaty:

In the meantime, the non-membership of these states in the PCT must be taken into account when considering patenting strategies, both by residents and foreigners interested in obtaining protection in these states. With regard to residents of these states who are not nationals of other PCT member states, it has already been pointed out above that it will be usual to include a national or resident of one of the PCT member states as an applicant. As for foreigners wishing to obtain patents in non-PCT states, they should opt for the traditional Paris Union route and be very careful not to exceed the 12-month time limit from the first filing. Priority could also be claimed from a PCT application involving a first filing.

CONCLUSIONS

The non-membership in the PCT of the five Latin American countries, especially Uruguay and Argentina, due to their income level and their essentially export-oriented economies with considerable innovative potential, is an anomaly that does not seem to be on the way to being reversed in the short term. For an external observer from the patent world, it would be logical for both countries to join the treaty in the near future, especially if one takes into account that within the 157 states that are now part of this treaty, there are countries of all levels of development and of all political orientations. Therefore, membership should not be so negative. On the other hand, the sovereignty of the states to adopt the decisions they consider most convenient must be respected, especially when similar arguments have been put forward by some European states for not joining the European patent with unitary effects.

Leopoldo Belda Soriano

One thought on “THE SOUTH AMERICAN ANOMALY IN THE PCT (PATENT COOPERATION TREATY)”