I am very fond of searching information about all kinds of patent-related issues, and from time to time I come across the “dark” side of patents, so to speak. Inspired by this, some time ago I wrote two entries devoted to patents and the conspiracy theories (1 y 2, in Spanish) and another one about “the patents that financed the SS” (also in Spanish).

Two years ago, The C.I.A (Central Intelligence Agency) announced that it had created a Database where 12 million pages of declassified documents had been made available to the general public.

The temptation was strong and I couldn’t help searching for information about patents among all that documentation that once had been classified by the C.I.A.

An example is provided by this document from 1948 which analyses in depth the system for the protection of inventions that was in force in the Soviet Union after the end of the Second World War. It was possible to obtain a patent proper or an inventor’s certificate, but apart from that peculiarity, the analysed legislation did not deviate much from what was common in most countries at the time.

This 1950 report consists of an English translation of the Patent Law of the new communist Chinese State. It referred to the “inventor’s certificates” and also to the so-called “special privileged rights”. Like in the Soviet Union, patents or similar rights on chemical products were forbidden. The same happened in Spain until the 7th of October 1992.

This document (1959) shows that Stalin’s death had eased USA-USSR relations, which made possible the signing of an agreement for the exchange of patents between the USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office) and the Soviet Technical Patent Library. “Official journals”, Soviet “inventor’s certificates” and U.S patents were exchanged as a result. It was a time when the publication of a patent document did not mean easy access to it. This other document mentions a more ambitious exchange: 614 Soviet Patents and 4,000 US patents.

This report (1947) informs us that the Russians had discovered 500,000 patent documents in the city library of Görtlitz (Saxony). They were dispatched to Moscow for analysis. These patents were probably part of all those patent documents that were scattered all over Germany during the last days of the Second World War, most of them ending up in a salt mine in Heringen and later in the hands of the U.S.A Army (see the entry “the patents that financed the SS”). Although most of those patents wound up in U.S libraries, this documents shows that part of them were also sent to Moscow.

The C.I.A also paid attention to the Japanese patents found after the occupation of Japan by the U.S troops. In this report a C.I.A agent suggested that those patents were translated into English, at least the abstracts, to assess whether they should be classified or made available to the North American Industry.

This message is another instance of how difficult it was to gain access to the patent documents published in Eastern European Countries during the Cold War. It revealed that fifteen patents on electronic inventions granted by East Germany in 1952 were available at the C.I.A library. The East Berlin Patent Office was under surveillance by C.I.A agents according to this report (1950) which discloses that even though the Office Director seemed to have quit the post and his address was in West Berlin, he was suspected of still working for the Patent Office in the Russian zone.

This document analyses the incorporation of the Soviet Union to the organization that preceded WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), the so-called Convention of Paris for Protection of Industrial Property. According to the report, it was the Soviet Union that actually benefited from joining this organization, much more than Western Countries. Once Stalin’s era was over, a time when patents were regarded as bourgeois stratagems to obtain monopolies, then a Soviet patent system was being developed. Joining the Paris Convention meant they could benefit from the priority right and file patent applications abroad. Even though Westerners could also file patent applications in the USSR, given the lack of private industry, they could not be exploited.

This document reproduces a Washington Post article from April 1985. From the underlining it seems it was thoroughly analysed. The Article refers to a documentation leak that took place in France and where Soviet agents were involved. A list of Western “military patents” the Soviets sought to obtain was among the information leaked. They were probably patents classified or kept secret, because they were of interest to the National Defense.

This report (1984) analyses the trade balance between the Soviet Union and Western countries in the field of patents.

The demise of the Soviet Union did not bring about a reduction in the interest in inventions that could be patented by Moscow. This brief note says that Radio Moscow had announced that the Russian Government sought to patent a “flying saucer”-shaped spacecraft, with a capacity of up to 2,000 passengers, which could take off and land anywhere, even on water.

The “flying saucer” was known as EKIP. Some aspects of the “flying saucer” were protected by the Russian Patent RU2033945C1. Eventually, it did not take off, mainly because of economic problems.

Thanks to this memorandum, we know that in 1971, the C.I.A had a so-called “Patents Board”, which mas made up of 6 voting members and at least a non-voting advisor. The “Patent Board” assessed whether the inventions were of interest and should be patented or not. This document shows that this regulation had a dissuasive effect and reduced the incentive to generate inventions by members of the organization, thus an amendment was suggested.

Among the documentation made available, numerous documents like this one are found where the USPTO was requested to declassify patents which were no longer of interest to the national defense. In this other document twenty patent applications are requested to be declassified whereas nine others must remain secret. It is possible to see the reasons why they were declassified:

Below is the first page of one of the patents initially kept secret US4669070 (when filed in 1979) and later declassified and published in 1987 because the technology was then general public knowledge.

This report (1950) discloses the existence of a device the C.I.A Communications Department was interested in. No patent had yet been granted on it, though two patent applications had been filed. The C.I.A was interested in the invention but did not know how to get hold of it. One option considered was that the device would be sold to the general public, then the invention would be bought by the Agency and modified in such a way that it could not be detected. Nevertheless, there was not a single entrepreneur interested in manufacturing it. Perhaps, this invention was an improved version of the ingenious Soviet device known as “the thing”.

In this letter (1956), a retired lieutenant , probably a patent agent at “Toulmin & Toulmin” (renowned for having been responsible for the Wright brothers’ patents) reported to the C.I.A due to the lack of attention paid by the USPTO direction and the Commerce Department, that there was a danger of the contents of pending patent applications being leaked. He mentions a letter from Hoover, the FBI Director, where he had stated that there was no legal base to act.

In this document, it is disclosed that the Government of the U.S.A. was sued for infringement of a patent (US2885248). The subject matter of that patent was claimed to be included in the F111 bomber. The C.I.A was requested to carry out a prior art search that could help achieve the annulment of the patent.

Among the declassified documentation there is also a lawsuit in which the owner of a patent seeks financial compensation for damages caused by the classification of his patent as secret.

“Pergamon International Information Corporation”, the Company that created “INPADOC”, the worldwide legal status database (now administered by the European Patent Office) sent a letter to the C.I.A. offering the information provided by the database, which included the English translation of patents from Japan, the Soviet Union, and most of the Eastern European Countries.

This report from 1985, which includes the working documents of an Intellectual Property group, shows that the creation of a common Patent Office for the entire American continent, inspired by the model of the European Patent Office, was considered.

This memo reveals that the procedure that was followed to carry out a prior art search by the C.I.A in 1966 was highly inefficient. An example is provided: the C.I.A was interested in obtaining a patent on a device. However, before filing the patent application, a prior art search was requested from an Army Office. The prior art search took more than a year, and eventually it showed that the invention did not meet the patentability requirements.

It seems that C.I.A members were aware of the requirements an invention had to meet in order for a patent to be granted. In this memorandum one can see how the inspection of an invention related to a binary code reader was organized in 1962. The need to sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) was raised in order to prevent a disclosure from affecting the novelty of a subsequent patent application.

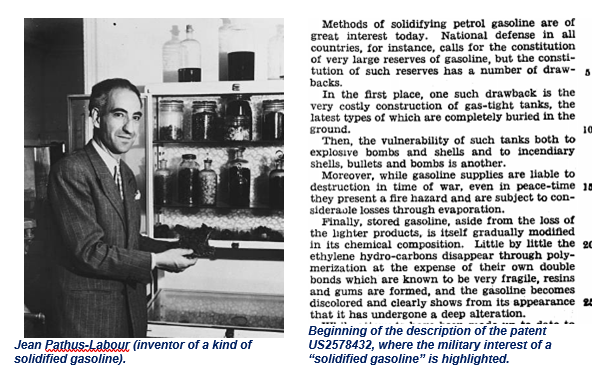

Other documents, like this report, show that one of the C.I.A’s goals was to obtain military information. In this case it was the so-called “solidified gasoline”, a kind of chimera of great military interest because it would be very easy to be stored or transported. Several attempts to obtain “solidified gasoline” are listed, such as the invention patented by Jean Pathus-Labour. The document ends by stressing that the results obtained in the U.S.A. had not been satisfactory, but the Soviet Union might have achieved it.

The economic side of patents was another objective of the C.I.A as revealed by the declassified information. In this memo (1985) the semiconductor field is analysed. The U.S.A were concerned about the lack of respect for the intellectual and industrial property in numerous semiconductor manufacturing states, especially in the Far East. In this other report (1988), the main concern was the lack of respect for patent rights on pharmaceutical products in Argentina in the 1980’s.

Information from Spain related to patents in some way is also found. The report is dated 1947. It is disclosed that shortly before the total defeat of Germany, the German company D.K.W (Dampf-Kraft-Wagen) had moved to Spain all its designs, materials and personnel needed to resume the manufacture of its vehicles there. The support of the Spanish Government made possible the manufacture in Barcelona of a model called “Eucort” (name derived from the entrepreneur Eusebio Cortés) by the Company “Automóviles Eurocort, S.A.”. The Eurocort had a two-cylinder motor and was exported to Argentina, one of the few countries with which Spain had commercial relations in those years.

The report also reveals that Carmencita Franco had received the first vehicle manufactured by the factory as a gift on the 11th September 1947. The C.I.A got information from “El Pardo” (The Palace where the dictator Franco lived) confirming that the “Eurocort” was a D.K.W vehicle with slight modifications aimed at passing it off as a Spanish vehicle. All that research had to do with the U.S concern about the transfer of German production means to Spain, including the obtaining of patents. The C.I.A feared this provided the numerous nazi exiles that had fled to Spain with economic resources

CONCLUSION

I hope this “patent archeology” exercise has been of interest to you. My goal was to make you aware of the kind of patent-related activities an Intelligence Agency such as the C.I.A. carries out. Anyway, the selection of documents I have provided is only a sample of all the documentation available in the C.I.A archives, by no means exhaustive, and surely additional searches, which I would encourage, would provide a cache of juicy stories about the world of patents and espionage.

Leopoldo Belda-Soriano

Proofread by Ben Rodway

One thought on “DECLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS: THE C.I.A AND THE PATENT WORLD”