Balzac and his work « les souffrances de l’inventeur » have a prominent place in the subject of “patents and literature”. It is the third part of the novel “les illusions perdues”. This novel by Honoré de Balzac was published in three installments during the period 1837-1843. The work was dedicated to Victor Hugo and is part of “The Human Comedy”, (1799-1850) (a series of novels and short stories). Balzac, who was one of the greatest figures of the French literature of the 19th century, was acquainted with the printing world. In 1825 he set up a printing business with other partners for the printing and selling of books. Throughout “Les souffrances de l’inventeur”, he shows his knowledge about this world on numerous occasions.

The main character is David Séchard, a printer’s son and a printer himself, who lived in Angoulême and continued the business founded by his father, with whom he had a complex relationship. In those years, first half of the 19th century, paper was made from a pulp where fibres from used clothing were mixed. As with all inventors, he was aware of a technological problem that had to be solved. It was a problem that the printing industry was facing not only in France but all over Europe.

“Des chiffonniers ramassent dans l’Europe entière les chiffons, les vieux linges et achètent les débris de toute espèce de tissus. Ce débris, triés para sortes, s’emmagasinent chez les marchands des chiffons en gros, qui fournissent les papeteries”

All over Europe there were ragmen that gathered used clothing, rags, and all kinds of textiles in order to supply paper manufacturers with raw material. That’s the origin of the French expression “se battre comme des chifonniers” (fight like ragmen) to refer to a violent fight.

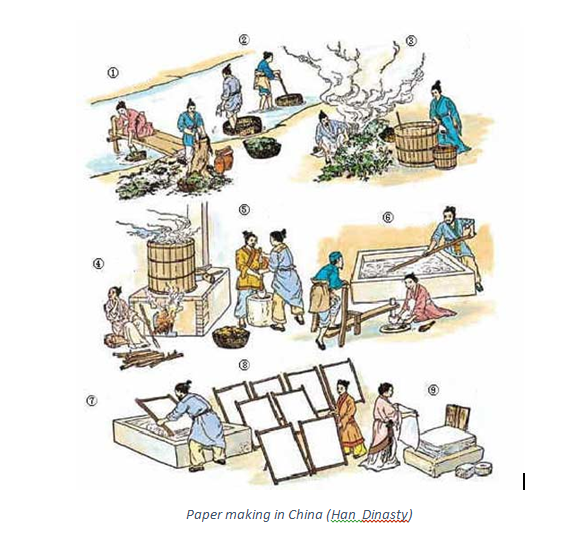

Balzac shows his knowledge of paper making when he describes the procedure for the manufacture of paper with all kinds of details:

“Le fabricant lave ses chiffons et les réduit en une bouillie claire qui se passe, absolument comme une cuisinière passe une sauce a son tamis, sûr un châssis en fer appelé ferme, et dont l’intérieur est rempli par une étoffe métallique au milieu de laquelle se trouve le filigrane qui donne son nom au papier. De la grandeur de la forme dépend alors la grandeur du papier”.”

Balzac tells us that the paper manufacturer washes the rags and turns them into a clear pulp that is passed through a sieve installed on an iron chassis where the watermark that gives the name to the paper is located.

Manufacture of paper from cellulose pulp obtained from wood was not invented until the second half of the 19th century. Before that breakthrough the manufacture of paper was very expensive. However, the paper obtained was of very high quality. The paper manufactured up to the late 19th century can easily be preserved for hundreds of years while nowadays paper, obtained from wood, disintegrates very rapidly in water and is deteriorated by moisture. For instance, this article reveals that the British parliament has been able to conserve all the laws passed (some of them from the 13th century) on vellum paper, obtained from sheepskin and equivalent to the “papier vélin” mentioned in the novel.

Nevertheless, once the Napoleonic wars were over, the publication of journals and books soared, and it was very hard to satisfy the demand of used clothes needed to manufacture such a vast amount of paper. Scarcity of textiles for the manufacture of paper had already been a problem in 1660 England when it was forbidden to use cotton shrouds for burials. Shrouds had to be made from wool because unlike cotton or linen it could not be used for making paper. As the narrator states, all printing professionals were aware of the need to change the way paper was manufactured.

“La papeterie s’en tiendrait au chiffon. Le chiffon est le résultat d’usage du linge et la population d’un pays n’en donne qu’une quantité déterminée. Il fallait, pour maintenir le papier à bas prix, introduire dans la fabrication du papier un élément autre que le chiffon.”

At that time numerous inventors were already working to replace used clothing as the main source of fibre for papermaking. The novel mentions that the French Patent Office had received over the previous 15 years more than 100 patent applications on new substances to replace rags as the raw material for paper production.

“Pendant ces quinze dernières années, le bureau chargé des demandes d’invention a reçu plus de cent requêtes de prétendues découvertes de substances à introduire dans la fabrication du papier.”

“Une foule de grands esprits a tourné autour de l’idée que je veux réaliser”.

The novel also refers to some of those attempts to replace rags as the source of fibre: recycling of used paper, cotton, straw. Nevertheless, either those materials were very expensive, or the quality of the paper obtained was not good enough. Recycling of paper was already available, but the cost was prohibitive.

“Madame Masson, dès 1794, essayait de convertir les papiers imprimés en papier blanc; elle a réussi, mais à quel Prix!”

As far as cotton was concerned, the quality achieved was not the one expected in those years, especially because It dissolved in water very rapidly.

“Salisbury tentait, en même temps que Séguin en 1801, en France, d’employer la paille à la fabrication du papier……. Le linge de fil est, à cause de sa cherté, remplacé par le linge de coton. En Angleterre on a commencé à fabriquer le papier du coton. Ce papier, se dissout dans l’eau si facilement qu’un livre en papier de coton, s’y mettrait en bouillie en y restant un quart d’heure.”

The inventor and main character David Séchard says that he already knew that in China paper was made from the fibres obtained from milling bamboo. Similarly he intends to use weeds, nettles and thistles, since they are cheap and can grow anywhere.

“Il va employer les orties, les chardons car pour maintenir le bon marché de la matière première, il faut s’adresser à des substances végétales qui puissent venir dans les marécages et dans les mauvais terrains.”

It seems that in those years Chinese labour was already much cheaper than in Europe. David Séchard was aware of the need to automate the grinding of fibres through the use of machinery.

“Le main d’œuvre n’est rien en Chine. Il faut remplacer les procédés du chinois par quelque machine”.

With the help of his invention, he also hoped to considerably reduce the weight and thickness of books up to 75% of those made of vellum paper.

“Si nous parvenions à fabriquer à bas prix du papier d’une qualité semblable à celui de la Chine, nous diminuerions de plus de moitié le poids et l’épaisseur des livres. Un Voltaire relié, qui, sur nos papiers vélins, pèse deux cents cinquante libres, n’en pèserait pas cinquante sur papier de Chine”.

He was aware as well of the increase in the demand for paper that would take place in the coming years, due to the boom in journalism.

“Une grande fortune, mon ami, car il faudra, dans dix ans d’ici, dix fois plus de papier qu’il ne s’en consomme aujourd’hui. Le journalisme sera la folie de notre temps.”

Of course, David had the well-known features of inventors: obsessive, hardworking and hopeful of achieving economic profitability.

“Il était né pour devenir inventeur. Il ne pouvait pas faire autre chose”.

“Dans trois mois je serai riche, répondit l’inventeur avec une assurance d’inventeur”

Sometimes, he feels overwhelmed by difficulty and uncertainty.

“Vous économiserez ainsi les privations, les angoisses du combat de l’inventeur contre l’avidité du capitalisme et l’indifférence de la société”

“Quelques doutes lui vinrent sur ses procédés. Ce fut une de ces angoisses qui ne peut être comprise que par les inventeurs eux-mêmes”

He is also blessed by fortune, which has been the origin of so many discoveries and inventions. Once, he was chewing one of the stems he got the fibres from and he found out that in order to achieve the desired result stems had to be ground the same way he was chewing them.

Il avait mâché par distraction une tige d’ortie qu’il avait mise dans de l’eau pour arriver à un rouissage quelconque des tiges employées comme matière de sa pâte………. Il se trouva dans les dents une boule de pâte. Il la prit sur sa main, l’étendit et vit une bouillie supérieure a toutes les compositions qu’il avait obtenues car le principal inconvénient des pâtes obtenues des végétaux est un défaut de liant. Ainsi la paille donne un papier cassant, quasi métallique et sonore. Ces hasards-là ne sont rencontrés que par les audacieux chercheurs des causes naturelles.

He points out that fortune is only found by the audacious inventors. Once the proper way of grinding fibres into high quality paper pulp had been identified, his goal was to attain the same result using machinery and a chemical agent.

“Je vais, se disait-il, remplacer par l’effet d’une machine et d’un agent chimique l’opération que je viens de faire machinalement”.

At that time, a few years after 1791, when the first French patent law, one of the first ones in the world, had been passed , inventors were aware already of the need to patent the invention if an economic return was to be obtained. In those years, before the appearance of the concept of “inventive step” or “non obviousness”, patent professionals were also aware of the fact that the requirement of novelty was not enough for a smooth functioning of the patent system. Competitors could avoid the infringement of patents by carrying out minute amendments (there is a reference to a simple screw). Besides, those variations could be protected as a “brevet of perfectionnement” or “perfectioning patent”.

“J’aurai tout à la fois un brevet d’invention et un brevet de perfectionnement. La plaie des inventeurs en France, est le brevet de perfectionnement. Un homme passe dix ans de sa vie à chercher un secret d’industrie, une machine, une découverte quelconque, il prend un brevet, il se croit maître de sa chose; il est suivi par un concurrent qui s’il n’a pas tout prévu, lui perfectionne son invention par une vis et la lui ôte ainsi des mains.”

Because of that, the inventor must be careful in order to protect not only the main invention but also possible improvements. David Séchard thought that he had found a possible improvement that must be patented as well. A layer of glue was applied to the paper to reduce permeability and make ink writing possible, but the coating had to be applied individually to each sheet of paper, with high labour cost. David also intended to protect an improvement that consisted of applying the glue in the same barrel where the pulp was and on a group of sheets and not individually.

“En inventant, pour fabriquer le papier, une pâte à bon marché, tout n’était pas dit! D’autres pouvaient perfectionner le procédé. David Séchard voulait tout prévoir, afin de ne pas se voir arracher une fortune cherchée au milieu de tant de contrariétés. Le papier de Hollande (ce nom reste au papier fabriqué tout en chiffon de fil de lin, quoique le Hollande n’en fabrique plus) est légèrement collé, mais il se colle feuille à feuille par une main d’œuvre qui renchérit le papier. S’il devenait possible de coller la pâte dans la cuve, et par une colle peu dispendieuse (ce qui se fait d’ailleurs aujourd’hui; mais imparfaitement encore), il ne resterait aucun perfectionnement à trouver. Depuis un mois, David cherchait donc à coller en cuve la pâte de son papier. Il visait à la fois deux secrets.”

Competitors are also present in the novel: the powerful Cointet brothers, owners of a big printing business who had heard about David invention. They tried to find out his secrets before a patent application was filed. They managed to do, at least partially, thanks to the information provided by one of David’s workers who was bribed.

“Les Cointet entendirent de lui les premières mots relativement à l’espionnage et à l’exploitation du secret que cherchait David”.

A common problem faced by all entrepreneurs and inventors is the difficulty of obtaining financing. David tried to get backing from his father, but the Cointet brothers, his competitors, made his father see how risky the investment would be: the cost of getting a patent would be 2.000 francs, it would be necessary to travel to Paris several times, and also the tests needed to implement the invention before the paper could be sold.

« Est-ce que vous croyez, mon bonhomme, que quand vous aurez donné dix mille francs à votre fils, tout sera dit? Un brevet d’invention coûte deux mille francs, il faudra faire des voyages à Paris; puis, avant de se lancer dans des avances, il est prudent de fabriquer, comme dit mon frère, mille rames, risquer des cuvées entières afin de se rendre compte.”

One of the Cointet brothers ends by telling David’s father, in order to prevent him from funding the invention, that there is nobody less trustworthy than an inventor.

“Voyez-vous, il n’y a rien dont il faille plus se défier que des inventeurs”.

David finds himself involved in an affair about a debt unpaid by his brother-in-law to the Cointet brothers, and he ends up in jail. Taking advantage of the delicate situation, the Cointet brothers managed to be included as applicants in David’s patent and in exchange David is freed. Below is the text of the patent transfer.

“Monsieur David Séchard fils, imprimeur à Angoulême, affirmant avoir trouvé le moyen de coller également le papier en cuve, et le moyen de réduire le prix de fabrication de toute espèce de papier le plus de cinquante pour cent par l’introduction de matières végétales dans la pâte, soit en les mêlant aux chiffons employés jusqu’à présent, soit en les employant sans adjonction de chiffon une société pour l’exploitation du brevet d’invention à prendre en raison de ces procédés, est formée entre Monsieur David Séchard fils et messieurs Cointet frères aux clauses et conditions suivantes….”

Eventually the Cointet brothers become the only owners of the patent when David renounces. He moves to the countryside where he leads a calm life, enjoying his father’s inheritance. The novel concludes by stating the importance the invention had for the French paper industry.

“La découverte de David Séchard a passé dans la fabrication française comme la nourriture dans un grand corps. Grâce à l’introduction de matières autres que le chiffon, la France peut fabriquer le papier à meilleur marché qu’en aucun pays de l’Europe.”

Conclusion

As far as the world of invention and patents is concerned, this novel is one of the first if not the first literary work that describes the adventures and misadventures of an inventor to protect his invention with that legal figure recently created called the patent. It is really amazing to see how around 200 years later, the ordeal an individual inventor has to go through in order for a patent to be granted and for the invention to be commercially exploited hasn’t changed that much.

Leopoldo Belda-Soriano

Proofread by Ben Rodway

Excelente artículo, muy interesante Leopoldo, gracias 😊

LikeLike